| Index |

| |||

| | |||

|

This past summer I had a wonderful time working on a research project with a group of talented undergraduates at the SMALL REU at Williams College. Together we were attempting to generalize some of my work on sets of integers which avoid geometric progressions. The original question I looked at was essentially "How large can a subset of the integers be and not contain any three term geometric progressions?" Having made some progress on that problem we were curious to see whether the ideas and results would apply in other rings beside the integers. In particular, we investigated what happens when looking at subsets of the algebraic integers in a quadratic number field.

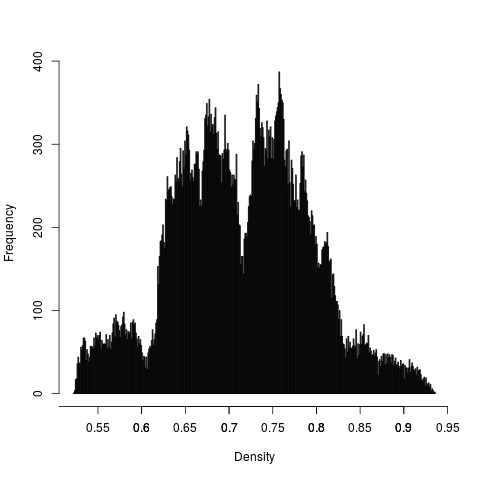

If you've never heard of quadratic number fields before, don't give up on me just yet, they aren't that scary. If you take the integers and make all of the possible fractions out of them you get what we call the rational numbers, sometimes written as ℚ. The rational numbers are great, in fact they are what we call a field meaning we can add, subtract, multiply or divide them, and still get another rational number. Sometimes though, the rational numbers aren't quite big enough. For example, you want to be able to take a square root, but you end up with something that isn't a rational anymore. You could go and use the real numbers (or you might need the complex numbers, if you want to take a square root of a negative number) but the real numbers aren't just a little bit bigger, they're a lot bigger. So suppose you don't want to go all the way to the real numbers. Maybe you just need to take the square root of two. You might just take the rational numbers and include the square root of two, but that wouldn't be a field anymore, because if you add 1 to the squareroot of two you get another thing that isn't rational. Or if you multiply that by 3 and so on. It turns out that if you take all of the numbers of the form a+b√2 where a and b can be any rational number you again have a field. We write this field as ℚ(√2). This field we get is called a number field. In fact it is a quadratic number field field because we got it by throwing in a square root of a rational. If we threw in a cube root instead we'd get a cubic number field and so on. One of the many nice things about quadratic fields is that every one of them can be found by constructing ℚ(√n) for some integer n. Now, when you go and make the rationals bigger, it turns out that the integers get bigger too. In fact, if we are working in ℚ(√2) we have to start thinking of numbers like 1+√2 as being integers as well. We call the set of all of the new integers we get the "Ring of algebraic integers." This object, the ring of algebraic integers, was where we wanted to ask our new question. Now, we wanted to know, "how large a subset of the ring of algebraic integers over a quadratic number field can you take and avoid three-term geometric progressions?" We found that many of the same ideas from the integers could be carried over. The details can be found in our paper which is available on the arXiv, submitted for publication, and also available here. One of the most interesting questions we looked at though, was "How big is the greedy set of algebraic integers?" The greedy set is constructed by including all of the small integers until the first time you try to include a number which would create a progression. Whenever that happens you skip the number and move on to including larger numbers that don't create a geometric progression. Over the integers the greedy set contains about 72% of the integers. Over different quadratic number fields this percentage can range anywhere from 51% to 94% and has a striking distribution, a histogram of the different densities for quadratic number fields ℚ(√-n) for 0 < n < 10000 is below.  |

|||

| |

|||